|

Papillary carcinoma |

|

Clinical presentation.

Papillary carcinomas are included in relatively fast growing nodules. The period lasting from the detection to the first visit in patients who were aware about a palpable tumor was in the range of 3-24 months with a median of 8 months in our practice. This is more fast than in the case of a benign nodule but more slowly compared with medullary carcinoma.

Palpation. As most malignant diseases, papillary carcinoma is presented generally by a firm or hard nodule. Nodules are not as hard as in the event of an anaplastic carcinoma. They are moveable, but in a less extent than benign nodules. In around 20% of cases we found enlarged, metastatic lymph nodes at the time of the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma. Palsy of the

recurrent nerve can be found in aggressive subtypes and in patients who requested evaluation only years after detection of the nodule. 10% of our patients presented with hoarseness.

Functional state. In contrast with other thyroid carcinomas, patients with papillary cancer are not infrequently subclinically hypothyroid. This is the consequence of the well-know association between lymphocytic thyroiditis and papillary carcinoma. There is a long-lasting and yet undetermined debate which is the cause and which is the consequence. Nevertheless, the concomitant thyroiditis is responsible for the usually mild and subclinical hypothyroidism. The presence of dysfunction is an interesting phenomenon but have practically no relevance in the diagnosis.

Ultrasonography.

Features with significantly increased risk of papillary carcinoma are listed in Table. From a practical point-of-view, the blurred borders of the nodule and the presence of microcalcifications are of the greatest diagnostic power.

Most papillary carcinomas occur in hypoechogenic nodules, it means more than 80% of cases. This proportion is less compared with e.g. medullary cancer or secondary thyroid carcinomas.

Irregular borders of a

hypoechogenic nodule is the most specific sign of papillary carcinoma.

Three types of irregularities have to be discussed. Ill-defined, blurred

border  is the most

important type. It means that we cannot decide where the nodule ends

and where the extranodular part of the thyroid begins. This type of

irregularity can be observed in the case of de Quervain's thyroiditis,

too. Serious differential diagnostic problems may arise in those

infrequent cases where the patient does not present typical clinical

signs of subacute thyroiditis. Naturally, in this situation FNAC is

mandatory.

is the most

important type. It means that we cannot decide where the nodule ends

and where the extranodular part of the thyroid begins. This type of

irregularity can be observed in the case of de Quervain's thyroiditis,

too. Serious differential diagnostic problems may arise in those

infrequent cases where the patient does not present typical clinical

signs of subacute thyroiditis. Naturally, in this situation FNAC is

mandatory.

The lobulated

margins of the nodule is another type of irregularity. The

cause for this phenomenon is either the infiltrative nature of the

tumor or the proliferation of the connective tissue. In the latter a

pseudonodular appearance can be observed similarly to that seen in

certain cases of a lymphocytic thyroiditis.

The lobulated

margins of the nodule is another type of irregularity. The

cause for this phenomenon is either the infiltrative nature of the

tumor or the proliferation of the connective tissue. In the latter a

pseudonodular appearance can be observed similarly to that seen in

certain cases of a lymphocytic thyroiditis.

The sharp irregular surface of the tumor is the less sensitive and specific type of the irregularity of the borders.

Microcalcification

is the second most characteristic sign  of papillary

carcinoma. It means that small bright punctate granules can be observed

within a hypoechogenic nodule. The differential diagnostic of punctate

granules includes the so called comet tail artefact and the

intranodular fibrosis. The former granule has a small characteristic

tail. In the case of intranodular fibrosis not only hyperechogenic

granules but hyperchogenic lines can be seen depending on the angle

between the fibrotic bundle and the transducer. Not infrequently a

clear distinction between various types of hyperechogenic granules

cannot be made.

of papillary

carcinoma. It means that small bright punctate granules can be observed

within a hypoechogenic nodule. The differential diagnostic of punctate

granules includes the so called comet tail artefact and the

intranodular fibrosis. The former granule has a small characteristic

tail. In the case of intranodular fibrosis not only hyperechogenic

granules but hyperchogenic lines can be seen depending on the angle

between the fibrotic bundle and the transducer. Not infrequently a

clear distinction between various types of hyperechogenic granules

cannot be made.

Coarse

calcification occur significantly more frequently in  the case of

papillary carcinoma then in benign nodules. The practical significance

is limited. Nevertheless, in certain cases the coarse calcification may

be the only suspicious sign. It was of great help in a case where a

small hypoechogenic nodule was found in an almost identically

hypoechogenic thyroid.

the case of

papillary carcinoma then in benign nodules. The practical significance

is limited. Nevertheless, in certain cases the coarse calcification may

be the only suspicious sign. It was of great help in a case where a

small hypoechogenic nodule was found in an almost identically

hypoechogenic thyroid.

Cystic

degeneration is a very common phenomenon in  the event of

a nodular goiter irrespectively of the nature of the lesion except for

medullary and follicular carcinoma, which only rarely contain cystic

areas. On the other hand, papillary carcinomas frequently present

cystic areas. The presence of microcalcification within the solid part

of a cystic nodule increases the likelihood of malignancy.

the event of

a nodular goiter irrespectively of the nature of the lesion except for

medullary and follicular carcinoma, which only rarely contain cystic

areas. On the other hand, papillary carcinomas frequently present

cystic areas. The presence of microcalcification within the solid part

of a cystic nodule increases the likelihood of malignancy.

Although the presence of

a halo sign suggests a  significantly

decreased risk of malignancy overall, the consequences of a detailed

analysis indicate that the situation is not so simple. First, if we do

not investigate encapsulated nodules, a high proportion of cancers will

be missed. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the absence of a halo

sign is not an independent risk factor. The absence of a halo decreases

the risk of malignancy only because this sign cannot be demonstrated in

the most frequently occurring malignant nodules, in hypoechogenic ones.

The demonstration of a halo sign is very difficult or even impossible

in most hypoechogenic nodules because the US appearance of the capsule

in such lesions is identical with the nodule. This is clearly proved by

the fact, that for follicular adenomas, which are encapsulated in 100%

of the cases, only 8.8% of the hypoechogenic nodules exhibit a halo

sign, whereas this feature can be demonstrated by US in 64.1% of all

other types of nodules. It is not surprising therefore, that the

presence of a halo sign significantly increases the risk of malignancy

in cases of moderately hypoechogenic nodules, while in hyperechogenic

nodules the presence or absence of a halo sign does not influence the

likelihood of malignancy.

significantly

decreased risk of malignancy overall, the consequences of a detailed

analysis indicate that the situation is not so simple. First, if we do

not investigate encapsulated nodules, a high proportion of cancers will

be missed. Moreover, our results demonstrate that the absence of a halo

sign is not an independent risk factor. The absence of a halo decreases

the risk of malignancy only because this sign cannot be demonstrated in

the most frequently occurring malignant nodules, in hypoechogenic ones.

The demonstration of a halo sign is very difficult or even impossible

in most hypoechogenic nodules because the US appearance of the capsule

in such lesions is identical with the nodule. This is clearly proved by

the fact, that for follicular adenomas, which are encapsulated in 100%

of the cases, only 8.8% of the hypoechogenic nodules exhibit a halo

sign, whereas this feature can be demonstrated by US in 64.1% of all

other types of nodules. It is not surprising therefore, that the

presence of a halo sign significantly increases the risk of malignancy

in cases of moderately hypoechogenic nodules, while in hyperechogenic

nodules the presence or absence of a halo sign does not influence the

likelihood of malignancy.

The taller-than-wide

sign is frequently mentioned in the  literature

because it also occurs significantly more frequently among malignant

lesions than among benign ones, but proved to be of less practical

significance in compared with micocalcification or surface

irregularities.

literature

because it also occurs significantly more frequently among malignant

lesions than among benign ones, but proved to be of less practical

significance in compared with micocalcification or surface

irregularities.

The situation is similar

as regards type 3 vascular  pattern,

i.e. the presence of increased intranodular blood flow. This phenomenon

occurs significantly more frequently among papillary carcinoma than

among benign lesions but the practical value is limited.

pattern,

i.e. the presence of increased intranodular blood flow. This phenomenon

occurs significantly more frequently among papillary carcinoma than

among benign lesions but the practical value is limited.

Elastography is nowadays a very popular field in thyroidology. Nevertheless, the results gained by different authors are hard to compare because of technical reasons. Moreover, it is questionable whether in the case of a lesion with a benign appearing elastographic pattern we could avoid FNAC.

We must keep in mind, that the task of ultrasonography is not to diagnose a carcinoma, but the detect a nodule with high enough risk of malignancy to perform aspiration cytology.

Cytological diagnosis

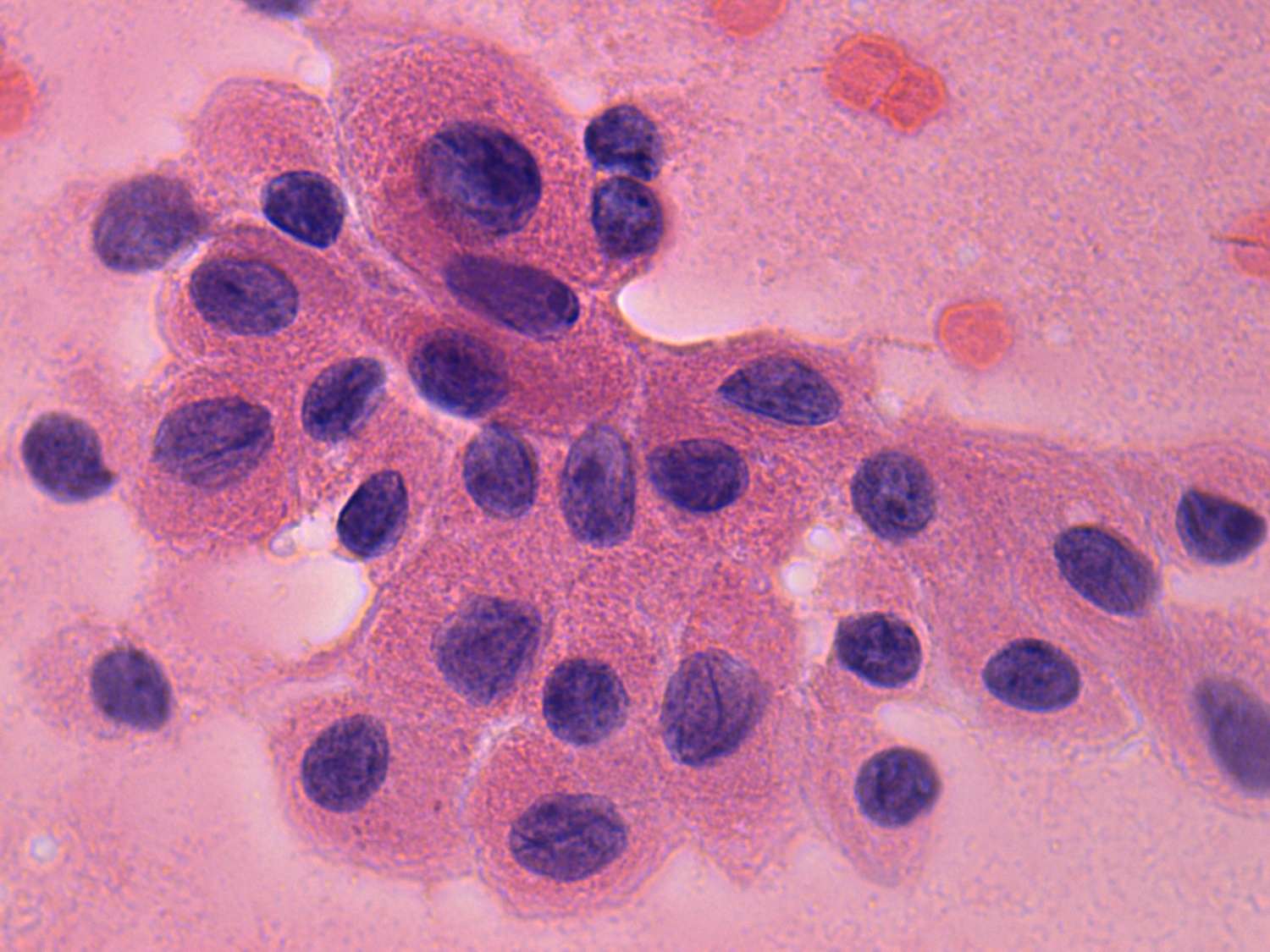

The main features of papillary carcinoma are as follows:

- Lack of colloid

- Cellular pattern

- Papillary fragments and monolayered sheets with disturbed pattern

- Atypical cells with mild to moderate pleomorphism

- Nuclear inclusions, grooves and scratchy chromatin structure.

- Distinct cell borders

- Presence of multinucleated cells

The first 2 features are not specific for papillary carcinoma and may be lacking.

Papillary fragments are 3-dimensional figures with sharp, geometric borders. In contrast with hyperplastic papilla, they lack peripheral vacuolization and projections. There is no tendency of cells at the edge of such clusters to dissociate.

Monolayered sheets are frequently found in PC. They are characterized by nuclear crowding and overlapping and loss of polarity of cells.

Nuclear inclusions are the most important clue in the diagnosis of PC. They re

At low power

The aspirates are usually rich in cells and contain little if any

colloid. The tumor cells occur in tumor fragments or  singly, in small

clusters or in cohesive sheets. The multilayered tumor fragments, the

papillae exhibit a sharp edge, with palisading of the

cells at the periphery, and a branching structure is often seen at low

power in the microscope. The nuclear details in cells from papillary

fronds are difficult to analyze in some cases, because of nuclear

crowding. In contrast with hyperplastic benign papillary clusters,

malignant papillae lack peripheral vacuolization and projections, and

also lack the tendency of peripheral cells to dissociate.

singly, in small

clusters or in cohesive sheets. The multilayered tumor fragments, the

papillae exhibit a sharp edge, with palisading of the

cells at the periphery, and a branching structure is often seen at low

power in the microscope. The nuclear details in cells from papillary

fronds are difficult to analyze in some cases, because of nuclear

crowding. In contrast with hyperplastic benign papillary clusters,

malignant papillae lack peripheral vacuolization and projections, and

also lack the tendency of peripheral cells to dissociate.

Another type of large cell clusters may be observed less often. These monolayered

sheets resemble those seen in nodular goiters. Sheets of

nodular goiters involve evenly-distributed nuclei without overlapping,

while the edges of these sheets are irr egular. More

important is the presence of naked, pyknotic nuclei close to the

sheets. In papillary cancer, the occurrence of dispersed cells is

infrequent, and the dispersed cells have abundant cytoplasm. Moreover,

cancer cells forming clusters display the characteristic nuclear

atypia, and are not evenly distributed. The edges of malignant

monolayered sheets may also be irregular.

egular. More

important is the presence of naked, pyknotic nuclei close to the

sheets. In papillary cancer, the occurrence of dispersed cells is

infrequent, and the dispersed cells have abundant cytoplasm. Moreover,

cancer cells forming clusters display the characteristic nuclear

atypia, and are not evenly distributed. The edges of malignant

monolayered sheets may also be irregular.

At high power

The cells of papillary cancer vary in size, but are larger than those

of nodular goiter cases. The variation in shape is also greater than in

benign cases. A great number of the nuclei are oval. This is one of the

characteristic features seen in papillary carcinoma. Small nuclei are

usually visible within the pale nuclei. The presence of large prominent

nucleoli is a rare phenomenon in the case of papillary carcinoma except

for the oxyphilic variant.

At high power

The cells of papillary cancer vary in size, but are larger than those

of nodular goiter cases. The variation in shape is also greater than in

benign cases. A great number of the nuclei are oval. This is one of the

characteristic features seen in papillary carcinoma. Small nuclei are

usually visible within the pale nuclei. The presence of large prominent

nucleoli is a rare phenomenon in the case of papillary carcinoma except

for the oxyphilic variant.

The chromatin is

finely dispersed, giving the nuclei a ground-glass appearance, a

feature commonly seen in smears stained by the Papanicolau method, but

less frequently by Wright-Giemsa method and only very infrequently in

smears stained by the hematoxylin-eosin method.

The chromatin is

finely dispersed, giving the nuclei a ground-glass appearance, a

feature commonly seen in smears stained by the Papanicolau method, but

less frequently by Wright-Giemsa method and only very infrequently in

smears stained by the hematoxylin-eosin method.

The nuclei not

infrequently exhibit a scratched appearance. This

sign is probably caused by the invagination of nuclear membrane as in

the case of inclusions and grooves. Another possible explanation is

that scratches correspond to condensed chromatin which is a frequent

finding in papillary carcinoma.

The nuclei not

infrequently exhibit a scratched appearance. This

sign is probably caused by the invagination of nuclear membrane as in

the case of inclusions and grooves. Another possible explanation is

that scratches correspond to condensed chromatin which is a frequent

finding in papillary carcinoma.

A peripheral

sharp dark ring of condensed chromatin is present in most of

the cases stained by the Papanicolau method . Even more important is

the presence of nuclear grooves and inclusions

within the nuclei. Both of these are artefacts,

and reflect intranuclear cytoplasmic invagination. The precise name

would be pseudo-inclusions and pseudo-grooves. From a practical point

of view, however, it seems reasonable to reserve the term

"pseudo-inclusion" for the inclusions of artefacts seen in benign

lesions. (If the smears are not wet-fixed, we can observe "typical"

nuclear inclusions. The other type of artefacts may be seen in cases

where vacuolization is present, even in euthyroid nodular goiter, for

hormonal reasons.)

A peripheral

sharp dark ring of condensed chromatin is present in most of

the cases stained by the Papanicolau method . Even more important is

the presence of nuclear grooves and inclusions

within the nuclei. Both of these are artefacts,

and reflect intranuclear cytoplasmic invagination. The precise name

would be pseudo-inclusions and pseudo-grooves. From a practical point

of view, however, it seems reasonable to reserve the term

"pseudo-inclusion" for the inclusions of artefacts seen in benign

lesions. (If the smears are not wet-fixed, we can observe "typical"

nuclear inclusions. The other type of artefacts may be seen in cases

where vacuolization is present, even in euthyroid nodular goiter, for

hormonal reasons.)

(In our opinion, this is one of the most important and problematic

fields in thyroid cyt ology and also in

pathology. For this reason we deal with it

in detail in a distinct

chapter.) Briefly, we consider the presence or absence of nuclear

inclusions and grooves is to be the most important factor in the

diagnosis of papillary cancer. In some cases, the inclusions and/or

grooves are rare, but we have seen them in all smears stained by the

Papanicolau method, with only one exception. These features may also be

observed in all other carcinomas of the thyroid, a fact which is not

problematic as concerns its diagnostic power. A matter of greater

concern is the observation that a relatively large number of nuclear

inclusions and grooves may be observed in oncocytic cells derived from

Hurthle-cell adenoma or Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

ology and also in

pathology. For this reason we deal with it

in detail in a distinct

chapter.) Briefly, we consider the presence or absence of nuclear

inclusions and grooves is to be the most important factor in the

diagnosis of papillary cancer. In some cases, the inclusions and/or

grooves are rare, but we have seen them in all smears stained by the

Papanicolau method, with only one exception. These features may also be

observed in all other carcinomas of the thyroid, a fact which is not

problematic as concerns its diagnostic power. A matter of greater

concern is the observation that a relatively large number of nuclear

inclusions and grooves may be observed in oncocytic cells derived from

Hurthle-cell adenoma or Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

The occurrence of nuclear inclusions and

grooves is greatly influenced by the staining method applied. Their

occurrence in hematoxylin-eosin-stained smears is very infrequent . For this

reason, this method of staining is not accepted in thyroid cytology.

Like other nuclear details, nuclear grooves and inclusions are best

seen in Papanicolau-smears. The Wright-Giemsa method is less sensitive

than the Papanicolau method in this field. On the other hand, the

former has better specificity.

. For this

reason, this method of staining is not accepted in thyroid cytology.

Like other nuclear details, nuclear grooves and inclusions are best

seen in Papanicolau-smears. The Wright-Giemsa method is less sensitive

than the Papanicolau method in this field. On the other hand, the

former has better specificity.

Other

features

Psammoma

bodies, which are generally regarded as a specific feature for

papillary carcinoma, are observed in about 20% of papillary carcinomas.

The classical picture of concentrically arranged, multilayered rings,

produced by changing the focus of the microscope is rarely seen. On the

other hand, benign thyroid lesions, most frequently multinodular

goiters, may also contain psammoma bodies. In the absence of cytologic

features suggestive of papillary cancer, isolated psammoma bodies are

unreliable as a predictor of papillary cancer.

Psammoma

bodies, which are generally regarded as a specific feature for

papillary carcinoma, are observed in about 20% of papillary carcinomas.

The classical picture of concentrically arranged, multilayered rings,

produced by changing the focus of the microscope is rarely seen. On the

other hand, benign thyroid lesions, most frequently multinodular

goiters, may also contain psammoma bodies. In the absence of cytologic

features suggestive of papillary cancer, isolated psammoma bodies are

unreliable as a predictor of papillary cancer.

In our practice, a definitive true psammoma body has been observed in

only 1 case of papillary cancer. In 12 other cases, we have seen dense

deposits resembling psammoma bodies. In all of these cases, other

features of the tumor were prominent. Hence, the occurrence of

(suspected) psammoma bodies was not of great help.

The

presence of multinucleated giant cells is observed in

a majority of cases (in our practice in 57% of the cases). Kini et al.

reported a similar incidence . In most cases, the presence or absence

of multinucleated giant cells is not of great relevance. It could have

been of great help in one of our false-negative cases. This patient

also had a hyperthyroidism, treated a with thyrostatic drug. The

cytologic picture revealed a nuclear enlargement, with a variation of

shape. Neither a papillary fragment nor nuclear inclusions or grooves

could be observed in smears stained by the hematoxylin-eosin and the

Wright-Giemsa methods. One year later, we performed a repeat FNAC and

at this time we were able to give the correct cytological diagnosis

(based on the occurrence of nuclear grooves in Papanicolau-stained

smears). A reviewing of the former smears highlighted two features: a

significant number of cells were oval, and some multinucleated giant

cells could be observed. Oval cells may be seen only sporadically in

hyperthyroidism. Moreover, analysis of the smears from patients with

hyperthyroidism demonstrated that the occurrence of multinucleated

giant cells is a quite sensitive and very specific feature as concerns

the presence of papillary cancer.

The

presence of multinucleated giant cells is observed in

a majority of cases (in our practice in 57% of the cases). Kini et al.

reported a similar incidence . In most cases, the presence or absence

of multinucleated giant cells is not of great relevance. It could have

been of great help in one of our false-negative cases. This patient

also had a hyperthyroidism, treated a with thyrostatic drug. The

cytologic picture revealed a nuclear enlargement, with a variation of

shape. Neither a papillary fragment nor nuclear inclusions or grooves

could be observed in smears stained by the hematoxylin-eosin and the

Wright-Giemsa methods. One year later, we performed a repeat FNAC and

at this time we were able to give the correct cytological diagnosis

(based on the occurrence of nuclear grooves in Papanicolau-stained

smears). A reviewing of the former smears highlighted two features: a

significant number of cells were oval, and some multinucleated giant

cells could be observed. Oval cells may be seen only sporadically in

hyperthyroidism. Moreover, analysis of the smears from patients with

hyperthyroidism demonstrated that the occurrence of multinucleated

giant cells is a quite sensitive and very specific feature as concerns

the presence of papillary cancer.

Cystic degeneration. The presence of a

small number of macrophages is quite often seen in papillary cancer. If

the tumor has undergone cystic degeneration, the correct cytodiagnosis

may be very difficult or even impossible. In these cases,

non-cytological  features

may be of help. The aspirated fluid

is brown in most cases of cystic papillary cancers. In one of our

cases, metastatic, cystic papillary cancer was suspected on the basis

of the elevated thyroxine content of the cystic fluid. US-guided FNAC

has a great role in this field. After evacuation of a cyst, we perform

a repeat US at once, with US-guided FNAC on the solid remnant of the

nodule. However, in a significant proportion of cystic thyroid nodule

cases, the FNAC report remains non-diagnostic. In those cases where the

cyst recurs, surgery should be considered as a possibility.

features

may be of help. The aspirated fluid

is brown in most cases of cystic papillary cancers. In one of our

cases, metastatic, cystic papillary cancer was suspected on the basis

of the elevated thyroxine content of the cystic fluid. US-guided FNAC

has a great role in this field. After evacuation of a cyst, we perform

a repeat US at once, with US-guided FNAC on the solid remnant of the

nodule. However, in a significant proportion of cystic thyroid nodule

cases, the FNAC report remains non-diagnostic. In those cases where the

cyst recurs, surgery should be considered as a possibility.

Focal

oncocytic metaplasia. This phenomenon is often seen, and is

mentioned by most published papers. On the other hand, it is not of

major significance, and in no way aids the diagnosis of papillary

cancer. It seems that oncocytic metaplasia (including its diffuse form,

the oxyphilic cell variant of papillary cancer) occurs somewhat, but

not

significantly more frequently in papillary cancer than in follicular

tumors or nodular goiter. The reason for this may be that degenerative

metaplastic changes occur more often in carcinoma cells as compared

with non-malignant lesions.

Focal

oncocytic metaplasia. This phenomenon is often seen, and is

mentioned by most published papers. On the other hand, it is not of

major significance, and in no way aids the diagnosis of papillary

cancer. It seems that oncocytic metaplasia (including its diffuse form,

the oxyphilic cell variant of papillary cancer) occurs somewhat, but

not

significantly more frequently in papillary cancer than in follicular

tumors or nodular goiter. The reason for this may be that degenerative

metaplastic changes occur more often in carcinoma cells as compared

with non-malignant lesions.

Scattered

lymphocytes in smears from papillary carcinoma are a common

finding. On the other hand a large number of lymphocytes may cause a

serious differential diagnostic problem first of all if follicular

cells present oxyphilic metaplasia. The differentiation between a

Hashimoto's thyroiditis with or without papillary carcinoma may be

impossible in cert

Scattered

lymphocytes in smears from papillary carcinoma are a common

finding. On the other hand a large number of lymphocytes may cause a

serious differential diagnostic problem first of all if follicular

cells present oxyphilic metaplasia. The differentiation between a

Hashimoto's thyroiditis with or without papillary carcinoma may be

impossible in cert ain

cases.

ain

cases.

We observed squamous cell metaplasia of papillary

carcinoma cells in around 3% of our cases. Differential diagnostic

problems arose in one of our cases but the thyroglobulin determination

in the wash-out of the needle decided the issue.

The  presence

of different population of cells on the same smear

may cause severe differential diagnostic problems. Fortunately, this is

a rare situation. If we gain the cytological sample from the adequate

localization than the dominant cell type on the smear comes from the

lesion in question and relatively small amount of cells comes from the

thyroid ventral to the nodule.

presence

of different population of cells on the same smear

may cause severe differential diagnostic problems. Fortunately, this is

a rare situation. If we gain the cytological sample from the adequate

localization than the dominant cell type on the smear comes from the

lesion in question and relatively small amount of cells comes from the

thyroid ventral to the nodule.

VARIANTS OF PAPILLARY CARCINOMA

Oxyphilic

cell variant of papillary cancer

(see chapter on oxyphilic tumors)

Follicular variant of papillary carcinoma

Diagnosis of this type

of cancer is more difficult. Papillary structures are not observed, and

the dominant follicular clusters resemble those seen in follicular

adenoma. The microfollicular structure is preserved in most cases.

Colloid is present in a relatively high number of the cases of the

follicular variant of papillary cancer. In its typical form, it appears

as thick globules. These features involve a risk of a false-negative

diagnosis. However, the nuclear details (the presence of nuclear

inclusions or grooves) are of great help  . Nevertheless,

we are of the opinion that, if only the nuclear details are suggestive

of papillary cancer, then a definitive cancer diagnosis may well be

false-positive (Mesonero 1998). 2 of our 4 false-positive

diagnoses were believed to be the follicular variant of papillary

cancer, but on histopathological examination both proved to be atypical

adenoma without any signs of invasion.

. Nevertheless,

we are of the opinion that, if only the nuclear details are suggestive

of papillary cancer, then a definitive cancer diagnosis may well be

false-positive (Mesonero 1998). 2 of our 4 false-positive

diagnoses were believed to be the follicular variant of papillary

cancer, but on histopathological examination both proved to be atypical

adenoma without any signs of invasion.

Accordingly, in this field we believe that if only nuclear details are

indicative of papillary carcinoma, the correct cytological report

should be a suspicion of (the follicular variant of) papillary

cancer. With regard to the relatively poor sensitivity of

intraoperative frozen sections in diagnosing this variant of papillary

carcinoma, the surgical procedure of choice in our practice when the

intraoperative frozen section is not conclusive is lobectomy of the

thyroid (see Chapter Guidelines to surgery).

Columnar and tall cell variant of papillary cancer

These variants are

represented by aggressive behaviour and a worse prognosis than for the

classical variant of papillary carcinoma.  The tall cell

variant exhibits cells with a height/width ratio > 2, single nuclei

and an abundant basophilic cytoplasm. These features resemble those of

Hürthle-cell tumors. The characteristic cytologic features of the

columnar cell variant are similar to those of the classical variant

except for a higher number of columnar cells and the presence of a

complex microfollicular pattern. The stratification of the nuclei

covering the tissue fragments and clusters of large cells with

vacuolated cytoplasm are also among the important cytologic features

mentioned in the literature. Metastatic adenocarcinoma is the most

important disease in the differential diagnostics of the columnar cell

variant. Immunocytochemistry is not always of help, because the cells

from columnar cell carcinoma are less differentiated.

The tall cell

variant exhibits cells with a height/width ratio > 2, single nuclei

and an abundant basophilic cytoplasm. These features resemble those of

Hürthle-cell tumors. The characteristic cytologic features of the

columnar cell variant are similar to those of the classical variant

except for a higher number of columnar cells and the presence of a

complex microfollicular pattern. The stratification of the nuclei

covering the tissue fragments and clusters of large cells with

vacuolated cytoplasm are also among the important cytologic features

mentioned in the literature. Metastatic adenocarcinoma is the most

important disease in the differential diagnostics of the columnar cell

variant. Immunocytochemistry is not always of help, because the cells

from columnar cell carcinoma are less differentiated.

Cytological differential diagnostics

Nodular goiter

This type of lesion

displays hyperplastic papillae in a significant number of cases. It is

usually possible to make a clear distinction between benign and

malignant papillarization TABLE.

It is not the type of the papillary frond that is the important

feature, but the presence or absence of the nuclear atypia

characteristic of papillary cancer. However, it may be difficult to

make a clear distinction when the follicular cells are not well

preserved (cystic degeneration) or metaplastic (oxyphilic cell

alteration). If well-preserved follicular cells are not seen, or only

sporadically, a differentiation between nodular goiter and papillary

cancer may be impossible. Additional  features

may be suggestive of the

nature of the disease. The presence of colloid, and the light colour of

the aspirated cystic fluid favour a benign disease. On the other hand

the dark-brown colour of the cystic fluid is of less relevance. If even

repeat FNAC is not diagnostic, then the size of the lesion and the age

and particularly the compliance of the patient help us to decide. If

the lesion is not larger than 2 cm, and the patient is young, we can

recommend follow-up (initially 6 months, and then once a year). If the

lesion grows in size, surgery is mandatory. On the other hand, if the

uncertainty causes the patient psychological stress, and we are unable

to relieve this, then we recommend operation even for lesions as small

as 1 cm in maximal diameter. In most cases, providing the patient with

detailed information is sufficient for reassurance, and only a few of

them then decide to undergo surgery.

features

may be suggestive of the

nature of the disease. The presence of colloid, and the light colour of

the aspirated cystic fluid favour a benign disease. On the other hand

the dark-brown colour of the cystic fluid is of less relevance. If even

repeat FNAC is not diagnostic, then the size of the lesion and the age

and particularly the compliance of the patient help us to decide. If

the lesion is not larger than 2 cm, and the patient is young, we can

recommend follow-up (initially 6 months, and then once a year). If the

lesion grows in size, surgery is mandatory. On the other hand, if the

uncertainty causes the patient psychological stress, and we are unable

to relieve this, then we recommend operation even for lesions as small

as 1 cm in maximal diameter. In most cases, providing the patient with

detailed information is sufficient for reassurance, and only a few of

them then decide to undergo surgery.

Hyperthyroidism

If a patient with

Graves-Basedow's disease exhibits a nodule (which is the situation in

around 25 % of our cases), FNAC must be performed. The risk of

papillary cancer in nodules in Graves-Basedow's disease is similar to

that for a euthyroid patient. The interpretation of the cytology is

somewhat more difficult, because the atypia caused by hyperthyroidism

and/or the thyrostatic agent  may

contribute to the cytological picture.

may

contribute to the cytological picture.

It must be borne in mind that either Graves-Basedow's disease or the

thyroid nodule itself is a condition which may indicat surgery. From a

clinical aspect, if a patient with hyperthyroidism has a nodule, the

question of surgery must be assessed very carefully. If there is any

doubt about the benign nature of the disease following microscopic

analysis, surgery should be proposed.

There is another problem. In autoimmune thyroid disorders, the presence

or absence of a nodule is not always clear. Increase in the

vascularization of the thyroid, as in hyperthyroidism, causes

alterations in the palpation: the thyroid becomes firm. The thyroid is

enlarged, and this enhances the extent of small irregularities in the

ventral contours of the gland. This is one of the conditions where the

palpation may overdiagnose a thyroid nodule. Moreover, the acute phase

of hyperthyroidism is the only condition where US may fail to detect

all of the lesions. It is well known that hyperthyroidism

demonstrates either diffuse hypoechogenicity or a patchy hypoechogenic

pattern. Thyroid malignancies primarily occur in nodules with low

echogenicity.) On the other hand, US may reveal discrete

echoabnormalities which are not nodules with potentially malignant

behaviour, but rather one of the appearance forms of Graves-Basedow's

disease. Thus, if there is no doubt that a nodule is present, but doubt

arises concerning its benign nature, surgery is mandatory. If the

presence of the nodule is questionable and the cytology is not clearly

benign, we again consider the indication of surgery. To avoid a failure

to detecting papillary cancer (which occurred in one of our cases), we

perform a second US 6 months after the beginning of the disease. At

this time, the low echogenicity caused by the hyperthyroidism has

decreased, and hypoechogenic nodules missed at the first US may be

detected.

Now back to the microscope. The atypia caused by hyperthyroidism is

reflected by nuclear enlargement, and a great variability in nuclear

size. However, the cells are characteristically round. Moreover,

nuclear grooves are not present. The characteristic vacuolization

caused by hyperthyroidism makes it difficult or impossible to interpret

nuclear vacuoles. The cells are arranged in loose cohesive monolayers,

which is a clear distinction from sheets of papillary cancer. In 2 of

our patients, typical papillary fragments with nuclear details

resembling those of papillary cancer were observed. These papillary

fronds were compact structures, which we observed in the hyperthyroid

phase but neither at the second FNAC, performed in a euthyroid state,

nor on histopathological examination. We proposed going on surgery

because US revealed discrete lesions in both patients. The

histopathology demonstrates benign disease in both cases, and

interestingly the final histological report was LT in both cases. The

hyperthyroidism was hashitoxicosis.

Hashimoto's thyroiditis

The reported incidence

of Hashimoto's thyroiditis in cases of papillary cancer varies greatly

in the literature (Kashima 1998). This is connected with

the problem of terminology in the various forms of LT (Selzer

1977 , Kashima 1998). Nuclear grooves, peripheral

sharp dark rings of condensed chromatin, and of course oxyphilic cell

changes, with nuclear atypia (even pronounced) are frequently

encountered in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. There are two conditions where

diagnostic difficulties arise. The first is, when there are only a few

lymphocytes in the smear, but US reveals a characteristic picture of LT

(diffuse hypoechogenic pattern without a discrete nodule). In these

cases, US is of great help. Although Hashimoto's thyroiditis is not

infrequently associated with small foci of papillary cancer, in our

practice no papillary cancer occurred in LT without discrete lesions on

preoperative US.

More concerns arise in the second condition, when we see nuclear

features resembling papillary cancer in a discrete lesion. Four factors

must be kept in mind in the decision-making: the number of lymphocytes

in the  smear, the

size and number of the lesions, the shape of the

lesions, and the cell type in which nuclear grooves are observed. TABLE If there

are many lymphocytes in the smear, the problem is

unfortunately not resolved and some patients with a benign disease may

undergo surgery. It may be mentioned here that the characteristic US

picture of papillary cancer, i.e. a hypoechogenic nodule with fine

granules, may be observed in more than 60 % of patient with the nodular

form of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. In the last 2 years we have frequently

decided on follow-up in questionable cases. If there are no conclusive

signs of papillary cancer, we perform repeat US (and cytology) 3 and 6

months later, and than every year. If the patient accepts our

suggestion, we do not give a definitive diagnosis after the first

examination. If the patient refuses follow-up, we give a diagnosis of

suspicion of papillary cancer. TABLE

smear, the

size and number of the lesions, the shape of the

lesions, and the cell type in which nuclear grooves are observed. TABLE If there

are many lymphocytes in the smear, the problem is

unfortunately not resolved and some patients with a benign disease may

undergo surgery. It may be mentioned here that the characteristic US

picture of papillary cancer, i.e. a hypoechogenic nodule with fine

granules, may be observed in more than 60 % of patient with the nodular

form of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. In the last 2 years we have frequently

decided on follow-up in questionable cases. If there are no conclusive

signs of papillary cancer, we perform repeat US (and cytology) 3 and 6

months later, and than every year. If the patient accepts our

suggestion, we do not give a definitive diagnosis after the first

examination. If the patient refuses follow-up, we give a diagnosis of

suspicion of papillary cancer. TABLE

This type of problem in the field of thyroid cytology is not emphasized

by others. The routine use of US explains why we are faced with this

problem relatively frequently.

Follicular adenoma

From a practical point

of view follicular adenoma is the only tumor in the thyroid which must

be the clearly distinguished from papillary cancer (in all other

thyroid  tumors

surgery can not be avoided). In most cases, the

distinction is not difficult. If we apply the Papanicolau method for

staining, a clear distinction between follicular adenoma and the

follicular variant of papillary cancer is possible on the basis of the

occurrence of nuclear inclusions and grooves. These nuclear features

are very rare in follicular adenoma. On the other hand,

hematoxylin-eosin staining is very insensitive for the detection

of nuclear grooves and inclusions. The Wright-Giemsa staining

procedure is better than the hematoxylin-eosin method, but not as good

as the Papanicolau method in this field.

tumors

surgery can not be avoided). In most cases, the

distinction is not difficult. If we apply the Papanicolau method for

staining, a clear distinction between follicular adenoma and the

follicular variant of papillary cancer is possible on the basis of the

occurrence of nuclear inclusions and grooves. These nuclear features

are very rare in follicular adenoma. On the other hand,

hematoxylin-eosin staining is very insensitive for the detection

of nuclear grooves and inclusions. The Wright-Giemsa staining

procedure is better than the hematoxylin-eosin method, but not as good

as the Papanicolau method in this field.

Follicular and oxyphilic tumors other than typical follicular adenoma

The suspicion of these

tumors is an absolute indication for surgery, so a clear distinction

between these tumors and pa pillary

cancer seems to be of little

practical

relevance. Nevertheless, in the case of a papillary carcinoma total

thyroidectomy is the treatment of choice while to perform total

thyroidectomy in the case of a benign adenoma is a great failure.

Occasionally, these tumors may be difficult to differentiate

from papillary cancer. This is particularly true for Hürthle-cell

tumors. There may sometimes be numerous nuclear grooves in oncocytic

adenoma. The round shape of the cells, and the prominent nucleoli of

uniform size may be of great help in avoiding a false-positive

cytological report when numerous grooves

pillary

cancer seems to be of little

practical

relevance. Nevertheless, in the case of a papillary carcinoma total

thyroidectomy is the treatment of choice while to perform total

thyroidectomy in the case of a benign adenoma is a great failure.

Occasionally, these tumors may be difficult to differentiate

from papillary cancer. This is particularly true for Hürthle-cell

tumors. There may sometimes be numerous nuclear grooves in oncocytic

adenoma. The round shape of the cells, and the prominent nucleoli of

uniform size may be of great help in avoiding a false-positive

cytological report when numerous grooves are

observed. Nevertheless, a

perfect solution to this

differential-diagnostic problem can not be

achieved in all Hurthle-cell adenoma cases. A definitive cytological

diagnosis of the oxyphilic variant of papillary cancer is acceptable

only in cases where characteristic features other than nuclear

inclusions and grooves are also be observed.

are

observed. Nevertheless, a

perfect solution to this

differential-diagnostic problem can not be

achieved in all Hurthle-cell adenoma cases. A definitive cytological

diagnosis of the oxyphilic variant of papillary cancer is acceptable

only in cases where characteristic features other than nuclear

inclusions and grooves are also be observed.